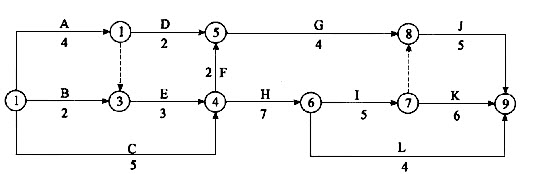

某建设工程合同工期为25个月,其双代号网络计划如图1所示。该计划已经监理工程师批准。

图1

[问题] 1.该网络计划的计算工期是多少为确保工期按期完工,监理工程师应重点控制哪些工作为什么

2.当该计划执行7个月后,监理工程师检查发现,施工过程C和施工过程D已完成,而施工过程E由于业主供应设备问题将拖后2个月。试分析E工作实际进度对计划的影响,为什么监理工程师应如何处理

3.如果工作E影响了原进度计划,业主不希望原计划延期,希望承包商采取赶工方案,为此承包商提出赶工所付出的技术措施费,更换机械费,夜间施工费等赶工费索赔。监理工程师能否同意该要求

4.为了满足业主对总工期要求,承包商提出的赶工方案是组织施工过程H、I、J、K进行流水施工。各施工过程在各施工段的流水施工节拍如表1所示。

表1

| 施工过程 | 施工段及流水节拍/月 | ||

| ① | ② | ③ | |

| H | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| I | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| J | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| K | 2 | 3 | 1 |

按照原进度计划中的逻辑关系,组织H、I、J、K均参与的流水施工的方案有几种流水施工工期各是多少计划的总工期各是多少

参考答案:

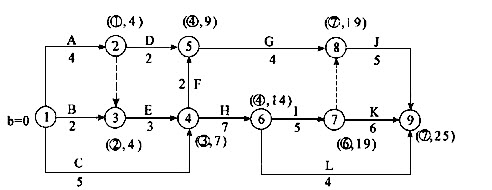

1.利用标号法找出关键线路和计算工期。

图3

计算工期Tc=25个月,关键线路见图3中粗箭线所示。

为确保工程按期完工,监理工程师应重点控制A、E、H、I、K五项工作。 因为它们均是关键工作,总时差均为零。

2.第7个月未检查时发现工作E由于业主供应设备问题将拖后2个月,超过其总时差 2个月(TFE=0),影响总工期2个月。由于造成E工作拖延的原因是业主,由承包商提出工程延期和相关费用赔偿申请,监理工程师核实后应批准承包商工程延期2个月和相关工程延期费用。如果业主不允许工程延期,监理工程师在同业主商议后,再同承包商协商赶工事宜。

3.由于E工作的拖延影响了原计划工期,业主要求承包商在后续工作中采取赶工方案,确保原25个月的工期,为此发生的一切赶工费均由业主承担。监理工程师应同意承包商所提出的费用要求。

4.组织H、I、J、K均参与的流水施工方案有两种:① H→I→J→K和②H→I→K→J (没有改变原计划的先后顺序)。

(1) 按H→I→J→K顺序组织流水施工。

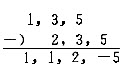

① 确定流水步距(采用“累加数列错位相减取大差值法”):

H和I:

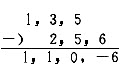

所以KH,I=4月

所以KH,I=4月

I和J:

所以KI,J=2月

所以KI,J=2月

J和K:

所以KJ,K=2月

所以KJ,K=2月

② 流水施工工期T1=[(4+2+2)+(2+3+1)]月=14月

③ 计算总工期如下。

因为第7个月未检查时,E工作拖后2个月,则E的完成时间为(7+2)月=9月,即第9个月未完成,所以H的最早开始时间为第9个月末。又由于H→I→J→K线路中,J工作的开始时间应为[9+(4+2)]月=15月,而另一条线路中工作G的最早完成时间为(9 +DF+DG)月=15月,所以G工作不影响流水施工中J工作的开始时间,则总工期为T= (9+14)月=23月。

或按线路确定。

E→F→G→J→K:7+

+DF+DG+KJ,K+DK=(7+2+2+4+2+6)月=23月

+DF+DG+KJ,K+DK=(7+2+2+4+2+6)月=23月

E→H→I→J→K:7+

+T2=(7+2+14)月=23月

+T2=(7+2+14)月=23月

E→H→L:7+

+DH+DL=(7+2+7+4)月=20月

+DH+DL=(7+2+7+4)月=20月

取最长的线路为计划的总工期:T=23月

(2) 按H→I→K→J顺序组织流水施工

① 确定流水步距:KH,I=4月

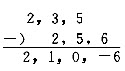

I和K:

所以KI,K=1月

所以KI,K=1月

K和J:

所以KK,J=3月

所以KK,J=3月

② 流水施工工期:T2=[(4+1+3)+(2+1+2)]月=13月

③ 计算总工期如下。

在H→I→K→J的流水线路中,J的最早开始时间为(9+4+1+3)第17个月末,而工作G的最早完成时间仍为(9+2+4)第15个月末,不影响J工作的开始,所以总工期为T=9+T2=(9+13)月=22月。

或采用线路法。

E→F→G→J:7+

+DF+DG+DJ=(7+2+2+4+5)月=20月

+DF+DG+DJ=(7+2+2+4+5)月=20月

E→H→I→K→J:7+

+T2=(7+2+13)月=22月

+T2=(7+2+13)月=22月

E→H→L:7+

+DH+DL=(7+2+7+4)月=20月

+DH+DL=(7+2+7+4)月=20月

故方案②的总工期T=22月。

由于两种顺序方案均满足原计划工期的要求,所以监理工程师可以批准该方案。

解析:

[解题思路]

1.对于第一个问题,可通过标号法或通过时间参数的计算求出施工工期和关键线路,关键工作,从而确定控制的重点。

2.对于第二个问题主要看拖延的工作是否是关键工作,拖延的时间是否超过其总时差来判断对工期的影响。同时监理工程师根据影响程序和造成拖延的责任进行分析。

3.对于第三个问题,监理工程师根据第2问分析的责任和承包商采取的赶工方案判定是否符合工期要求。

4.对于第四个问题,首先分析有几种流水施工组织方案,然后对每种方案采用非节奏流水组织的方式计算流水施工工期。再在已推迟工作E完成时间的基础上计算出总工期。