(46) History tells us that in ancient Babylon, the cradle of our civilization, the people tried to build a tower that would reach to heaven. But the tower became the tower of Babel, according to the Old Testament, when the people were suddenly caused to speak different languages. In modern New York City, a new tower, that of the United Nations Building, thrusts its shining mass skyward. (47) But the realization of the UN’s aspirations—and with it the hopes of the peoples of the world—is threatened by our contemporary Babel: about three thousand different languages are spoken throughout the world today, without counting the various dialects that confound communication between peoples of the same land.

In China, for example, hundreds of different dialects are spoken; people of some villages have trouble passing the time of day with the inhabitants of the next town. In the new African state of Ghana, five million people speak fifty different dialects. In India more than one hundred languages are spoken, of which only fourteen are recognized as official. To add to the confusion, as the old established empires are broken up and new states are formed, new official tongues spring up at an increasing rate.

In a world made smaller by jet travel, man is still isolated from many of his neighbors by the Babel barrier of multiplying languages. Communication is blocked daily in scores of ways. Travelers find it difficult to know the peoples of other nations. Scientists are often unable to read and benefit from the work being carried on by men of science in other countries. (48) The aims of international trade, of world accord, of meetings between nations, are blocked at every turn; the work of scholars, technologists, and humanists is handicapped. Even in the shining new tower of the United Nations in New York, speeches and discussions have to be translated and printed in the five official UN language—English, French, Spanish, Russian and Chinese. Confusion, delay, suspicion, and hard feelings are the products of the diplomatic Babel.

The chances for world unity are lessened if, in the literal sense of the phrase, we do not speak the same language. (49) We stand in dire need of a common tongue, a language that would cross national barriers, one simple enough to be universally learned by travelers, businessmen, government representatives, scholars, and even by children at school.

Of course, this isn’t a new idea. Just as everyone is against sin, so everyone is for a common language that would further communication between nations. (50) What with one thing and another—our natural state of drift as human beings, our rivalries, resentments, and jealousies as nations—we have up until now failed to take any action. I propose that we stop just talking about it, as Mark Twain said of the weather, and do something about it. We must make the concerted, massive effort it takes to reach agreement on the adoption of a single, common auxiliary tongue.

(47) But the realization of the UN’s aspirations—and with it the hopes of the peoples of the world—is threatened by our contemporary Babel: about three thousand different languages are spoken throughout the world today, without counting the various dialects that confound communication between peoples of the same land.

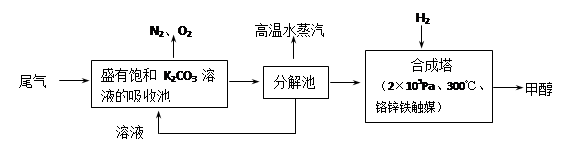

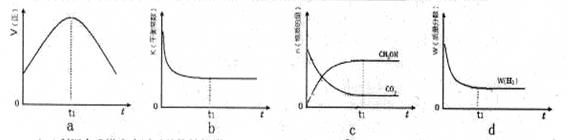

CH3OH(g)+H2O(g),在密闭条件下,下列示意图能说明反应进行到t1时刻时达到平衡状态的是 (填字母序号)

CH3OH(g)+H2O(g),在密闭条件下,下列示意图能说明反应进行到t1时刻时达到平衡状态的是 (填字母序号)

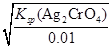

=1.56×10-8;0.01mol/L CrO42-,开始沉淀时c(Ag+)=

=1.56×10-8;0.01mol/L CrO42-,开始沉淀时c(Ag+)= =3.0×10-5。故Cl-先沉淀。

=3.0×10-5。故Cl-先沉淀。