问题

单项选择题

水电站的地下厂房围岩为白云质灰岩,饱和单轴抗压强度为50MPa,围岩岩体完整性系数Kv=0.50。结构面宽度3mm,充填物为岩屑,裂隙面平直光滑,结构面延伸长度7m。岩壁渗水。围岩的最大主应力为8MPa。根据《水利水电工程地质勘察规范》(GB50487—2008),该厂房围岩的工程地质类别应为下列何项所述()

A.Ⅰ类

B.Ⅱ类

C.Ⅲ类

D.Ⅳ类

答案

参考答案:D

解析:

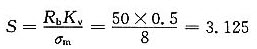

根据《水利水电工程地质勘察规范》(GB 50487—2008)式(N.0.8),计算岩体围岩强度应力比:

根据附录N.0.9计算围岩总评分:

①岩石强度评分A查表N.0.9-1,得A=16.7。

②岩体完整程度评分B查表N.0.9-2,得B=20。

③结构面状态评分C查表N.0.9-3,得C=12。

④地下水状态评分D查表N.0.9-4,得D=-7.26。

⑤各评分因素的综合确认:

B+C=32>5,A=16.7<20,取A=16.7;B+C=32<65,取B+C=32。

查表N.0.7得工程地质类别为Ⅳ类。