对自然的认识是一个不断修正和完善的过程。请阅读以下材料回答:(11分)

材料一:2400多年前古希腊学者亚里士多德提出,植物生长发育所需的物质全部来自土壤;

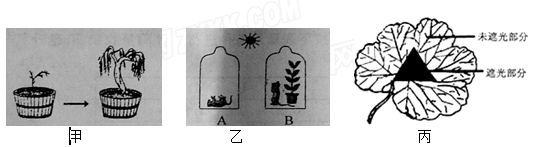

材料二:17世纪,比利时海尔蒙特把一棵2.5千克的柳树种在装有90千克泥土的水桶里,只浇水。经过五年,再次称量,柳树质量已达80多千克,而泥土减少却不到100克,如图甲所示;

材料三:18世纪,英国普利斯特利通过如图乙实验发现,A钟罩内的小鼠很快死亡,B钟罩内的小鼠却可存活较长时间;

材料四:1864年,德国萨克斯发现绿色植物在光下还能合成淀粉等物质。1897年,人们首次把绿色植物的上述生理称为光合作用。

(1)如果亚里士多德的观点成立,则海尔蒙特的实验结果为 。

(2)普利斯特利实验说明了 。

(3)如今,依据碘能使淀粉变 色的特点,常通过检测淀粉来判断植物是否进行了光合作用;在“绿叶在光下制造淀粉”的实验中,将一盆天竺葵放置黑暗处一昼夜后,选其中一个叶片,用三角形的黑纸片将叶片的上下两面遮盖起来,如图丙所示,置于阳光下照射一段时间,摘下叶片,经过酒精脱色、漂洗,最后在叶片上滴加碘液,请分析回答:

1)将天竺葵放在黑暗处处理一昼夜的目的是 。

2)叶片的一部分遮光,一部分不遮光,这样处理可起到 作用。

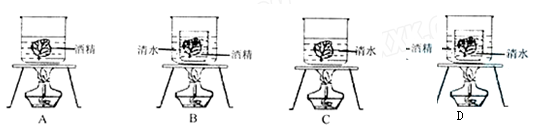

3)下图中对叶片进行酒精脱色的装置正确的是 。当实验结束取出小烧杯后,可观察到酒精和叶片的颜色分别是 和 。

4)在脱色后的叶片上滴加碘液,变蓝的是图丙叶片中 部分,

由此说明 。

5)在我们的实验室里,利用这盆植物不适合完成下列哪项实验( )

A.观察叶片结构

B.探究二氧化碳是光合作用的原料

C.探究光合作用产生氧气

D.探究叶片正面和背面的气孔数目

(1)土壤质量明显减少(从具体质量的数值予以比较等类似答案也可)

(2)绿色植物能释放供动物维持生命的气体(植物能产生氧气等类似答案均给分)

(3)蓝 1)将原有淀粉运走耗尽 2)对照(对比、比较) 3)B 酒精呈绿色,叶片呈黄白色 4)未遮光 绿叶在光下制造淀粉 5)C

题目分析:(1)亚里士多德认为植物生长发育所需的物质全部来自土壤,如果他的观点成立,则海尔蒙特的实验结果应该为木桶里土壤的质量明显减少;

(2)英国普利斯特利实验是:A钟罩内没有绿色植物,小鼠很快死亡,B钟罩内有绿色植物,小鼠却可活较长时间,这说明绿色植物能够为小鼠的呼吸提供氧气;

(3)淀粉遇碘变蓝色是淀粉的特性,人们常用淀粉的这个特性来鉴定淀粉的存在,在检测植物是否进行了光合作用时也用到碘液,

实验步骤:暗处理→部分光照→光照→摘下叶片→酒精脱色→漂洗加碘→观察颜色,

1)暗处理:将盆栽的天竺葵放到黑暗处一昼夜,目的是把叶片中的淀粉全部转运和消耗,这样就说明了,实验中用碘液检验的淀粉只可能是叶片在实验过程中制造的,而不能是叶片在实验前贮存;

2)部分遮光:用黑纸片把叶片的一部分从上下两面遮盖起来,然后移到阳光下照射.是为了设置对照,此实验中的变量是光照,目的:看看照光的部位和不照光的部位是不是都能制造淀粉;

3)几小时后,摘下叶片,去掉遮光的纸片,把叶片放入盛有酒精的小烧杯中,隔水加热,使叶片中的叶绿素溶解到酒精中,叶片变成黄白色,故B装置是正确的,脱色过程中,盛有叶片烧杯中的液体溶解了叶绿素逐渐变成绿色,脱色后的叶片呈现的颜色是黄白色;

4)用清水漂洗叶片,再把叶片放到培养皿里,向叶片滴加碘液.稍停片刻,用清水冲掉碘液,观察叶片颜色发生的变化,被黑纸片遮盖的部分没有变蓝色,未遮光部分变成蓝色,淀粉遇碘变蓝色;

5)氧气具有助燃的性质,但在实验室里,这盆植物光合作用产生的氧气不好收集,故选C。