In 1930, W. K. Kellogg made what he thought was a sensible decision, grounded in the best economic, social and management theories of the time. Workers at his cereal plant in Battle Greek, Mich. were told to go home two hours earlier, every day for good.

The Depression-era move was hailed in Factory and Industrial Management magazine as the "biggest piece of industrial news since Henry Ford announced his five-dollar-a-day policy." It’s believed that industry and machines would lead to workers’ paradises where all would have less work, more free time, and yet still produce enough to meet their needs.

So what happened Today, instead of working less, our hours have stayed steady or risen- and today many more women work so that families can afford the trappings of suburbia. In effect, workers chose the path of consumption over leisure.

With unemployment at a nine-year high and many workers worded about losing their jobs- or forced to accept cutbacks in pay and benefits -- work is hardly the paradise economists once envisioned.

The modern environment would seem alien to pre-industrial laborers. For centuries, the household -- from farms to "cottage" craftsmen -- was the unit of production. The whole family was part of the enterprise, be it farming, blacksmithing, or baking. "In pre-industrial society, work and family were practically the same thing," says Gillis.

The Industrial Revolution changed all that. Mills and massive iron smelters required ample labor and constant attendance. For the first time, work and family were split. Instead of selling what they produced, workers sold their time. With more people leaving farms to move to cities and factories, labor became a commodity and placed on the market like any other.

Innovation gave rise to an industrial process based on machinery and mass production. The theories of Frederick Taylor, a Philadelphia factory foreman, led to work being broken down into component parts, with each step timed to coldly quantify jobs that skilled craftsmen had worked a lifetime to learn. Workers resented Taylor and his stopwatch, complaining that his focus on process stripped their jobs of creativity and pride, making them irritable. Long before anyone knew what "stress" was, Taylor brought it to the workplace- and without sympathy.

The division of work into components that could be measured and easily taught reached its apex in Ford’s River Rouge Plant in Dearborn, Mich., where the assembly line came of age. To maximize the production lines, businesses needed long hours from their workers. But it was no easy to sell.

Labor leaders fought back with their own propaganda. For more than a century, a key struggle for the labor movement was reducing the amount of time workers had to spend on the job.

Between 1830 and 1930, work hours were cut nearly in half, with economist John Maynard Keynes famously predicting in 1930 that by 2030 a 15-hour workweek would be standard. While work had once been a means to serve God, two centuries of choices and industrialization had turned work into an end in itself, stripped of the spiritual meaning that sustained the Puritans who came ready to tame the wilderness.

By the end of the 1970s, companies were reaching out to spiritually drained workers by offering more engagement while withdrawing the promise of a job for life, as the American economy faced a stiff challenge from cheaper workers abroad. By the 1990s, technology made working from home possible for a growing number of people. Seen as a boon at first, telecommuting and the rapidly proliferating "electronic leash" of cell phones made work inescapable, as employees found themselves on call 24/7. Today, almost half of American workers use computers, cell phones, E-mail, and faxes for work during what is supposed to be nonwork time. Home is no longer a refuge but a cozier extension of the office.

When the stock market bubble burst and the economy fell into its recent recession, workers were forced to re-evaluate their priorities. They want a better quality of life; they’re asking for more flextime to spend with their families.

But there’s still the question of fulfillment. A recent study shows that work doesn’t satisfy workers’ deeper needs. "We expect more and more out of our jobs," says Hunnicutt. "We expect to find wonderful people and experience all around us." |

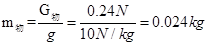

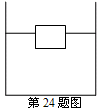

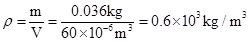

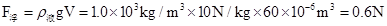

(2) 此木块的重力是多少?

(2) 此木块的重力是多少? ;

; ;

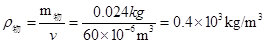

; ,

, ;

; ,

,