问题

选择题

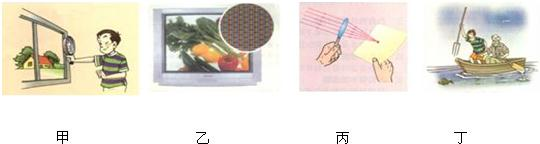

下面是晓丽从生活中收集到的一些光现象实例,以下说法正确的是( )

A.图甲隔着放大镜看物体,物体总是放大的

B.图乙电视画面的颜色是由红、绿、蓝三种色光组成的

C.图丙凸透镜只能使平行于主光轴的光会聚

D.图丁有经验的渔民叉鱼时对着看到的鱼叉

答案

A、当物体在二倍焦距看到缩小的像;物体在一倍焦距和二倍焦距之间,能看到放大的像;物体在一倍焦距以内能看到放大的像.错误.

B、电视画面由红、绿、蓝三种原色合成各种色光.正确.

C、凸透镜能使所有的光线会聚.错误.

D、鱼的实际位置在看到像的下面,有经验的渔民叉鱼时,要对着看到的鱼的下面叉去.错误.

故选B.